Most of us have a fairly resolute idea of our rights, as exhibited by our forceful reactions when delivered an unfair situation. We’ve all faced these testing times, where something we feel we deserved didn’t happen for us, or (perhaps worse) a bad situation happens that we most certainly didn’t deserve. It’s part and parcel of life. Being an eldest child, my exposure to life’s cruel nature has been long and gruelling, I’m sure all the firstborns among us will complain of facing stricter standards than our younger siblings. (Ironically, the younger siblings only had hand-me-downs, and those of you who are only children are thinking it’s unfair we had siblings to squabble with!) This is perhaps trivial, but the sense of anger when in an ‘unfair’ situation extends much further than sibling-related drama.

Perhaps you’re rolling your eyes, but if you’re honest with yourself how do you react when you pull the short straw of life? For example: if a colleague receives credit for something of your doing, or if you’re scammed by a sham email? Often, our reactions are primarily anger and frustration. We’ve all been told ‘Life’s not fair’ (some add, ‘and then you die’, for good measure), but few of us are content with this.

The anger caused by these situations stems from our sense of entitlement, the extent to which we (feel we) have a right to something. There are lots of rights we are legally ‘entitled’ to, such as the freedom of speech. There are other rights that exist not in words or legislation, but in the invisible contracts of relationships, and in our minds. My colleague told me he understands that a vegan/vegetarian lifestyle is better for the planet, but it would never be his lifestyle, as humans before us got to enjoy life and so he would enjoy his. Doubtless, his sense of personal entitlement to an ‘enjoyable’ life clashes with some of our senses of what is fair to our fellow man, animals, and the environment. When we feel entitled to something, we are far more likely to be passionate about it, and to care deeply when we do not receive it. If meat eating were outlawed, no doubt my colleague would be angry – perhaps you would be too, perhaps you feel you are entitled to eat what you want.

When we feel entitled to something, we are far more likely to be passionate about it, and to care deeply when we do not receive it.

On the other hand, there are few of us who decry injustice biased in our favour. I have been on the receiving end of some incredible unprovoked generosity. Recently I was slipped some money and a scrawled message: ‘Only for use as a treat’. It wasn’t fair that I should receive this gift, in no way was I entitled to it, nor did I have a desperate need for it. It was unfairly bestowed, completely unprompted and undeserved, but most gratefully received. It was a gift, it was a grace; I got something undeserved, just because. Had I felt entitled to it, would I have felt the gratitude I did? It is probable that I would have taken it for granted.

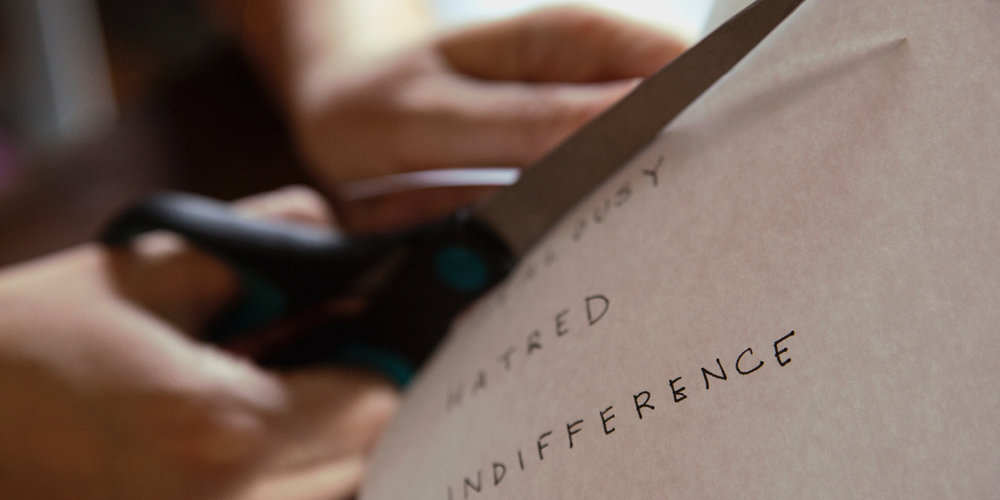

Herein lies the problem: entitlement is gratitude’s nemesis, the Scar to its Mufasa, threatening to throw it to the slaughterous stampede of the wildebeest’s hooves at the soonest possible chance. Entitlement is ugly, and it is dangerous.

Should you look up ‘how to be happy’, actively being grateful for things generally appears on the list. This perspective enlightens me to blessings already present in my life. I did nothing to deserve the good fortune I was born into: a roof over my head, food on the table, parents who love each other. I didn’t earn it, I was never entitled to it, and it’s an amazing gift.

What can you attribute your own good fortune to? Maybe you don’t feel fortunate, but we overlook so much – like the breath in our lungs, running water, a laugh shared. Perhaps this is simply ‘good fortune’, the product of a benevolent universe, or fate’s mystic powers, or karma – you were a great person (or plant) in your previous life. There are gifts woven into every element of the universe, giving us reason to be grateful. To me, these gifts are too much and too personal to be chance, and I am convinced that I never could have been a good enough plant to receive the favour that is the stars in the sky, air to breathe, and people to love. My belief in an omnipresent, omnipotent, benevolent God grounds my gratitude, giving me someone to be grateful to, and a reason for the wonder that is life, and this world. It’s not that life has been easy, or struggle free (see previous article), but with the realisation I am not entitled to anything and that there is nothing I can think of that I really deserve, the gratitude soon wells up, in spite of the challenges.